Seasons play a significant role in disrupting aviation operations. Summers are characterized by intense thunderstorms and heat. For instance, density-altitude-related performance degradation resulted in major airlines such as American Airlines canceling approximately 40 flights in Phoenix, AZ (PHX) as temperatures reached 120°F in June 2017. The fall season is ideal for air transportation and is typically characterized by the least number of flight cancellations. The winter season presents numerous challenges including aircraft icing, decreased aircraft braking efficiency, and strong frontal systems. While thunderstorms contain aviation hazards such as icing, lightning, microbursts, precipitation (including hail), turbulence, visibility obscuration, and windshear, fronts enable thunderstorms by providing two ingredients for convective activity, i.e., instability in the atmosphere and a lifting mechanism. Over the continental United States (CONUS), the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Pacific Ocean provide the necessary moisture sources and thus the final ingredient necessary for convective activity.

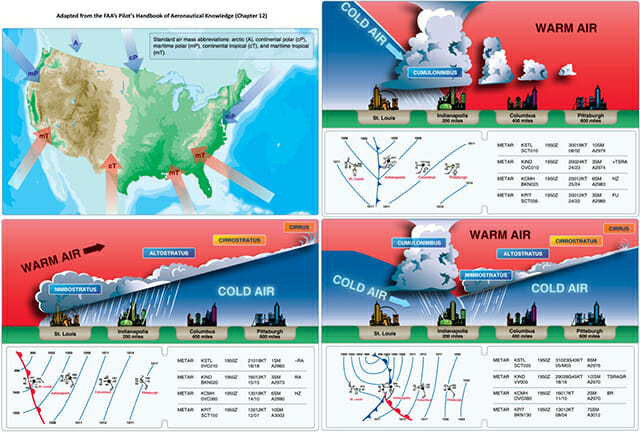

Air masses are classified based on their temperature and moisture content, and the interaction of these air masses typically results in significant weather for aviation. Continental air masses are typically dry while maritime air masses are moist. Arctic (A) or polar (P) air masses are cold, and tropical (T) air masses are warm. Therefore, the four primary air masses are Continental Tropical (cT), Maritime Tropical (mT), Continental Polar (cP) and Maritime Polar (mP). The strong baroclinicity (i.e., the misalignment of the gradients in pressure at temperature) results in mid-latitude cyclones sweeping through the CONUS with bi-weekly frequency.

Cold fronts are fast moving (25-30 mph) and are most often characterized by a steeper gradient (1:100). The steep gradient promotes the development of cumulus clouds resulting in thunderstorms and associated hazards. Faster moving cold fronts are typically accompanied by hazardous squall lines ahead of the cold front. Warm fronts are typically slower moving (10-25 mph) and have a shallower gradient (1:200). The clouds associated with warm fronts are comparatively stratiform. The overtaking of a warm front by a cold front results in an occlusion. The air mass characteristics determine the type of precipitation (e.g., freezing rain, hail, rain, or snow) associated with the front. Therefore, understanding the overall position, movement, and characteristics of the front including freezing levels will substantially aid in the overall situational awareness for an aviator. My future articles will provide a detailed account of the different types of fronts and recommendations for pilots.

Weather is an important factor in flight operations. Therefore, pilots should review the overall “big picture” and their understanding of the location and movement of weather fronts. While crossing a frontal boundary may be the shortest path between your origin and destination, it may not be the wisest. Respecting aircraft limitations and passenger comfort should be considered before crossing a frontal boundary. Bottom line: As an aviator, exercising good judgment and risk management coupled with lifelong learning promotes the overall safety of flight.