When we think of aviation safety, we usually think of nothing at all. We think of the millions of flights, the billions of passengers and the months or years that go by between accidents and typically accept aviation as being a “safe” form of travel. This is especially true of the public at large, who may have no technical knowledge of aviation whatsoever and who almost certainly have no idea about the complexities involved in taking a tube of aluminum, loading it with fuel, passengers and bags and hurtling it through the sky at hundreds of miles an hour during all types of weather, at all hours of the day.

However, anybody in the aviation industry knows the extreme amount of complexity and coordination required to safely move airplanes all over the world and one of the primary technologies that allows it to happen is CRM or “Crew Resource Management.” Like most technologies, CRM has been an evolving concept and one that was, unfortunately, born out of necessity as a result of several high profile and completely preventable accidents.

“Email Your Safety Thoughts To Scott.Stahl@aerocrewnews.com”

In aviation, we spend hours and years training for inevitable and catastrophic events that could happen to us in order to insure that we are not just ready for them if they do happen, but also to insure that we are adequately trained and proficient if they do. Engine failures, control failures, partial and total landing gear systems failures, and many more are things that all professional pilots have trained for repeatedly and frequently.

However, after the advent of Cockpit Voice Recorder and Flight Data Recorder technology, safety investigators quickly started to determine that most accidents were actually caused by a category of factors knows as “Human Factors.” Human Factors is a broad way to classify how humans perceive, receive input, process data, reason, and ultimately interact with other humans and their environment. Understanding how humans interact with their environment is critical to safety and was critical to the development of CRM because it was found that a majority of accidents could have been prevented by improving the way the people on the airplane interacted with each other. This became especially apparent as airplanes became more complicated, automated, reliable and capable as the rate of accidents caused by the airplanes themselves became less and less. This coupled with several major accidents that didn’t involve an airplane fault at all really highlighted the need for improvements on the human interface side of the equation. Crew Resource Management was a way to ensure that all stakeholders in a flight had a way to ensure that everyone had equal input and weight into the decisions that were made and that teamwork and advocacy were encouraged rather than discouraged.

The accident at Tenerife where two 747’s collided, the brand new Eastern L-1011 that crashed in the Everglades due to lack of crew coordination and the United Airlines DC-8 that ran out of fuel in Portland all highlighted the failures in human interaction that resulted in these accidents with perfectly good airplanes.

Another photo of Eastern Airlines Flight 401. Photo used with permission from the FAA Lessons Learned website, lessonslearned.faa.gov

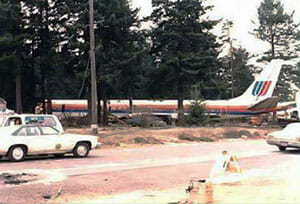

Once researchers started looking into the human environment on the airplane, it was determined that by and large aviation operations did not foster open communication and advocating by all flight crew members. Some companies even promoted such a culture where it was acceptable for the Captain to be a totalitarian figure on board the airplane. Obviously, not fostering open communication or placing much value on the experience or viewpoint of other crew members was detrimental to safety, and according to the FAA, human error was a factor in 60-80% of all aviation accidents. It was also found that there were no fundamental procedures for workload management such as Pilot Flying and Pilot Monitoring. The lack of communication and lack of crew equality could be clearly seen in the United DC-8 accident where both the First Officer and the Flight Engineer had repeatedly prompted the Captain about their worsening fuel state with no action. The workload management issues were apparent in the Eastern Airlines L-1011 crash when it became clear that all flight crew members were intensely focused on a minor problem (burned out lightbulb) while the aircraft descended into the ground with nobody monitoring the airplane. Perhaps the most specific example of the issues with the human operating environment was the Tenerife accident precipitated by an impatient Captain who willfully disregarded controller instructions related to departure by taking off without a clearance to do so. Ironically, this was the initial accident that prompted psychologists to start looking into what would evolve into CRM concepts, but it wasn’t until the 1978 United Airlines DC-8 crash that CRM concepts would be formally recommended as the result of an accident, and then ultimately rolled out in training for the first time by United Airlines in 1981.

Photo of United Airlines Flight 173, after it crashed into a wooded area while troubleshooting a landing gear anomaly. Photo used with permission from the FAA Lessons Learned website, lessonslearned.faa.gov

By the 1990’s CRM had proven so effective that it was practically a world standard and is something today that is just an inherent part of the operating environment. Not only is it mandated by the FAA, but it has become a normal part of the fabric of everyday aviation operations. Once its effectiveness had been determined amongst flight crews, it was expanded to include dispatchers, mechanics, ramp ops, ATC controllers and anybody else who had a stake in the safe outcome of a flight. This resulted in the change from “cockpit resource management” to “crew resource management.”

In the next issue, we will discuss the foundational concepts of CRM and how they apply to a multi-crew environment in aviation operations.

Of course, Safety Matters is best with reader participation so any submissions with questions, thoughts or topics for discussion are always encouraged and may be sent to scott.stahl@aerocrewsolutions.com.