When dinosaurs ruled the earth and I was training for my commercial ticket, I had an ancient and grizzled instructor named Ernie. Ernie was a gruff, old-school pilot whose favorite training aid was a well-aimed slap to the back of his student’s head. We beat up the skies around Lancaster, California, in a surplus T-34A in the late 1980s as I prepared for my commercial pilot checkride.

When dinosaurs ruled the earth and I was training for my commercial ticket, I had an ancient and grizzled instructor named Ernie. Ernie was a gruff, old-school pilot whose favorite training aid was a well-aimed slap to the back of his student’s head. We beat up the skies around Lancaster, California, in a surplus T-34A in the late 1980s as I prepared for my commercial pilot checkride.

I thought about Ernie the other day when I read an NTSB decision from August 2016; FAA v. El Khoury and Abbassi (NTSB, 8/2/2016). The case involved the investigation of a flight school in Van Nuys, California. Two pilots lost their certificates in the aftermath. Their case reminded me of a time when I had to make a decision in my own fledgling career.

Defendant Abbassi was the Director of Flight Operations for the flight school. Defendant El Khoury was a commercial pilot training to become a CFI; in fact, he had already twice failed the CFI practical exam.

.

A new student, the son of an airline pilot, began his private pilot training with the school and was assigned to El Khoury despite his lack of a CFI certificate. They flew four training flights together. The student’s father became suspicious as to El Khoury’s qualifications and insisted on seeing his CFI certificate. When none was produced, the father called the FAA.

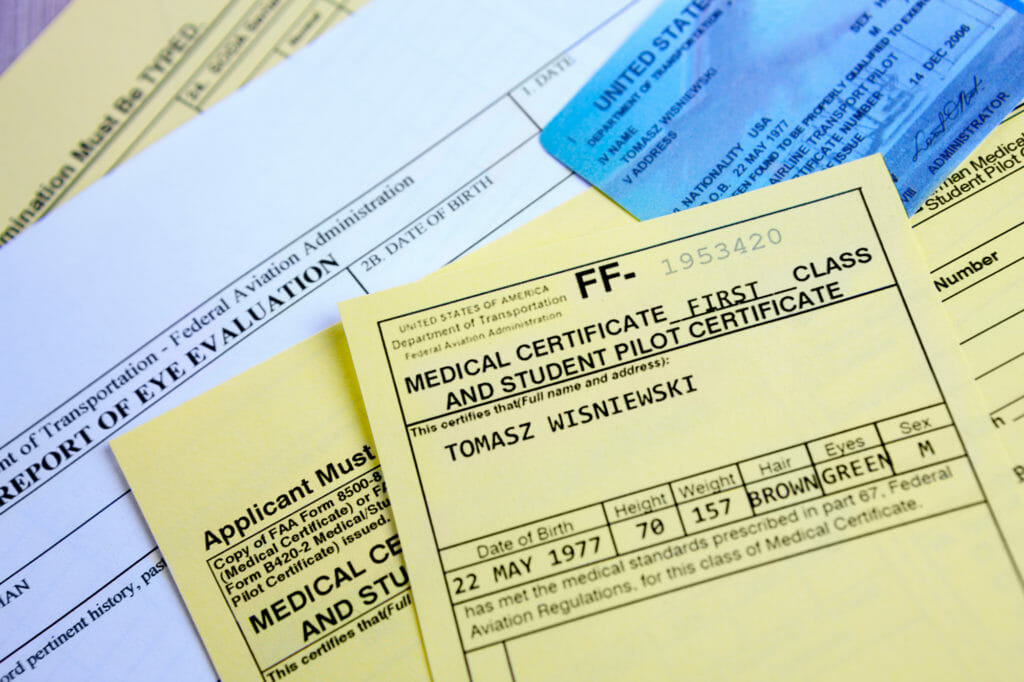

In the subsequent investigation, the inspector found that El Khoury would instruct in training flights, and then endorse the student’s logbook using a rubber stamp of Abbassi’s signature, CFI number, and expiration date to sign the entries. The CFI expiration date on the stamp, however, was wrong, so at some point Abbassi himself went back and corrected the expiration dates – thus making it impossible for him to claim that he was ignorant of what El Khoury was doing.

The relevant regulation is 14 C.F.R. 61.59: “Falsification, reproduction, or alteration of applications, certificates, logbooks, reports, or records.” In a nutshell, no person can make or cause to be made a fraudulent or intentionally false logbook entry, and violations can lead to suspension or revocation of an airman certificate, rating or authorization.

The NTSB uses a three-prong test to determine intentional falsification. The FAA must prove that the airman: (1) made a false representation; (2) in reference to a material fact; and (3) with knowledge of the falsity of the fact. (Hart v. McLucas, 535 F.2d 516, 519 [9th Cir. 1976]).

The NTSB uses a three-prong test to determine intentional falsification. The FAA must prove that the airman: (1) made a false representation; (2) in reference to a material fact; and (3) with knowledge of the falsity of the fact. (Hart v. McLucas, 535 F.2d 516, 519 [9th Cir. 1976]).

The student had witnessed Khoury using Abbassi’s stamp, leaving very little doubt as to the facts of the case. Logbook entries indicating required dual instruction are definitely material facts. The complete record can be found at https://www.ntsb.gov/legal/alj/OnODocuments/Aviation/5785.pdf.

Both pilots lost all their certificates via emergency order of the FAA, and that order was upheld on appeal to the NTSB. ACN