We have all been there – realizing an instrument or some equipment on the airplane is inoperative, potentially ruining the viability of our flight. From a legal standpoint, there are several considerations tied to making a go or no-go decision after the discovery of inoperative equipment. Do you know what they are?

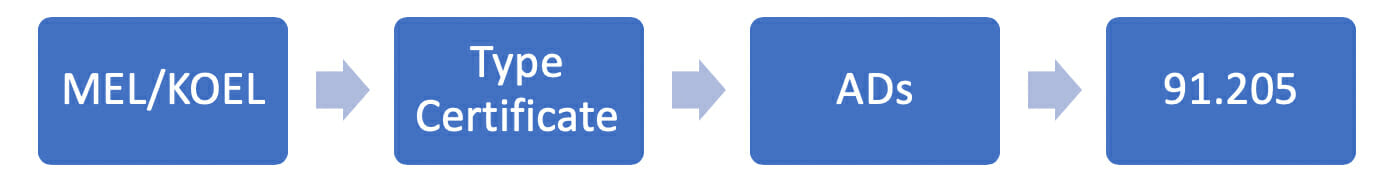

First, you must determine if the equipment is required per the “Minimum Equipment List (MEL)”, or the “Kinds of Operation Equipment List (KOEL)”. KOELs are found on the POH or AFM, as they are aircraft (make/model) specific. If the equipment is required per either list, the aircraft is unairworthy. The next step is to review the Aircraft Type Certificate. If not required by the Type Certificate, determine if the equipment is required by an Airworthiness Directive (AD). ADs are regulatory in nature. These bulletins are issued by the FAA and can be easily accessible via the FAA website. Finally, the last element to consider is FAR 91.205. This regulation lists the required instruments and equipment, both under VFR and IFR. The flow chart below summarizes the sequence:

Once you have reviewed these elements, there is an additional key regulation often forgotten: 91.213. Subparagraph (d) focuses on placarding of inoperative instruments and equipment (excerpted here).

“. . . The inoperative instruments and equipment are –

(i) Removed from the aircraft, the cockpit control placarded, and the maintenance recorded in accordance with § 43.9 of this chapter; or

(ii) Deactivated and placarded “Inoperative.” If deactivation of the inoperative instrument or equipment involves maintenance, it must be accomplished and recorded in accordance with part 43 of this chapter; and . . .”

What does this mean to you? It states the inoperative equipment must be deactivated and placarded, or fully removed. Placarding (an INOP sticker) is not sufficient. Placarding is tied to deactivating. A mechanic might be needed to perform the deactivation. Likewise, if deactivation is not feasible and the item needs to be removed, such process must be conducted by an authorized mechanic under Part 43 and properly logged.

For airman testing purposes, under the Airworthiness Requirements task of the Private Pilot ACS, the applicant must: “Apply appropriate procedures for operating with inoperative equipment in a scenario given by the evaluator.” The examiner will most likely choose a hypothetical inoperative instrument or equipment, to then evaluate your airworthiness knowledge. An example is included below:

“You turn the master switch on, turn on all the external flights, and perform a walk-around. You notice that the landing light is inoperative. Now what?

[Source: ACS Tips for Evaluators]

Show your understanding of this question by considering all the previous elements discussed in a logical sequence.

Lastly, because an equipment might not be legally required, it does not mean it is safe to conduct the flight. A risk assessment is imperative (identification, followed by mitigation). Not every pilot perceives risk the same way. Consider comparing a newly certified pilot vs. another with hundreds of hours of experience. Ask yourself: Do I feel comfortable flying without this instrument/equipment? What if the conditions inflight turn from VFR to IFR? Am I placing myself in a dangerous position? Safety must always be the top priority. Safety always supersedes legality. While regulations exist to protect us, they cannot possibly cover all circumstances and contexts. It is our responsibility to have personal minimums without allowing external pressures to influence our decisions.