October 18, 2021: John Hauser, a sophomore at the University of North Dakota, takes off from Grand Forks International Airport in a Piper Archer. It is a normal solo, nighttime takeoff and landing practice flight. The weather is good, the aircraft has passed its preflight inspection, and John is celebrating passing a recent commercial pilot test. It has the marks of a typical Monday evening training flight. Except this time, John sends a text message to his parents, Alan and Anne, saying he loves them and goodbye.

Alarmed by the odd message, John’s parents attempt to text and call his cell phone. No response. Now frantic, they call the Grand Forks airport and receive heartbreaking news. The airport has evidence from their radar that a University of North Dakota plane had gone into a rapid descent and crashed in a field south of Grand Forks. Hours later, it would be confirmed that it was John’s plane and that he had perished. Alan and Anne immediately drove to Grand Forks, retrieving letters John had written to them that had been left in his residence. These letters confirmed the tragedy of John’s death. He had taken his own life. Admitting to suffering in silence and hiding his mental health struggles from his parents, he feared that if he were to seek basic mental health care and treatment, he would be grounded from flying and kept from a career in aviation. Feeling trapped by the decision of seeking care and subjecting himself to the FAA’s mental-health policies or being able to continue his joy and passion for flying, he posed a request to his parents:

If there’s anything you could do for me, get the FAA to change their rules on pilots seeking help with their mental health. I know it would change a lot of things for the better and it would help a lot of people out.

Health Care Avoidance

John’s tragic struggles highlight the normalized deviance of health care avoidance in the aviation community. When given the decision to seek basic care, a study conducted by Dr. Billy Hoffman concludes that 56.1% of pilots show behavior in line with avoiding medical treatment, choosing to suffer in order to continue to fly. This issue is magnified when looking at the disparity between genders, with female pilots avoiding health care treatment at a staggering 83.7%.

This avoidance behavior contradicts what mental health professionals recommend for basic mental-health treatment. The FAA, along with research and practical studies, show that the earlier you can intervene in a mental-health condition, the easier and more effective treatments are going to be in returning that person to a normal mental-health state. Basically, the earlier a person can get into talk therapy or onto a prescription drug treatment for their mental-health ailments, the faster that person will be able to return to fly.

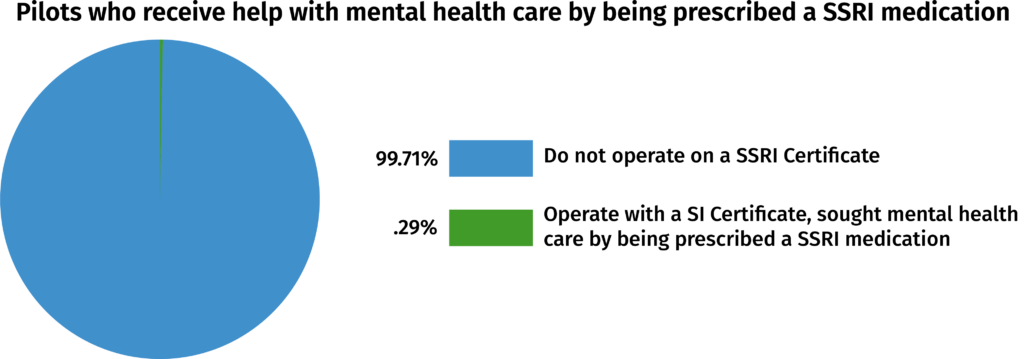

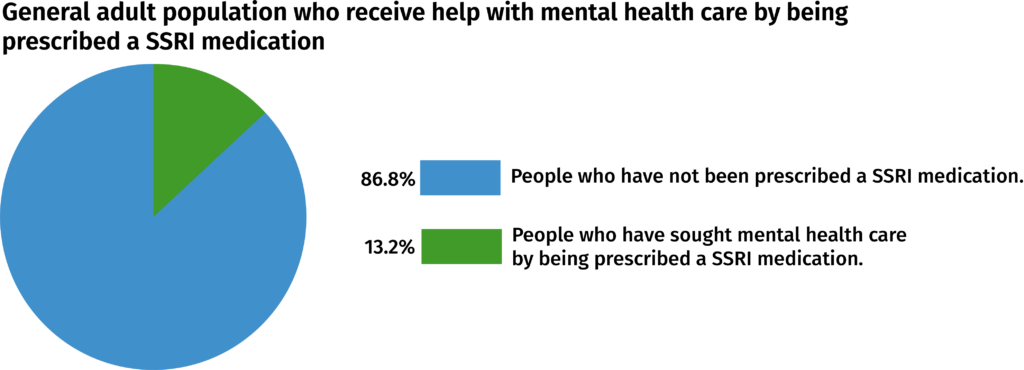

The current number of pilots operating under an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) Special Issuance Certificate compared to the SSRI usage to the adult population in the United States is statistically impossible. The most current FAA numbers state that around 500 pilots are currently operating with a SI Certificate. According to the CDC, from 2015-2018 roughly 13.2% of the adult population had sought treatment for mental health care by being prescribed an SSRI medication. That data extrapolated across the roughly 174,000 Airline Transport Pilot certificates in the United States would mean that there should be almost 23,000 pilots who are currently being treated with an SSRI, roughly a 22,500-person discrepancy from the FAA numbers.

Clearly, pilots choose not to seek treatment from basic, proven, and safe mental-health practices. This compounds their issues and can eventually result in a mental-health crisis to avoid the draconian policies and procedures the FAA currently uses to determine if pilots are fit to fly after a treatable mental-health diagnosis. Right now, the skies are safe despite the FAA’s policies, not because of their policies.

FAA and Federal Government Response

The FAA consistently states that only a few personality disorders are disqualifying and that ultimately only .1% of the approximately 385,000 annual medical applications they receive are denied certification. This statistic glosses over the reality that pilots experience when they attempt to obtain a special issuance medical certificate for SSRI or NDRI (norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors) treatment. These pilots often wait years for the FAA’s response to their medical applications after spending thousands of dollars out of pocket on neuropsychological testing, neurocognitive testing, personality testing, and psychiatric evaluations. The pilot’s board-certified psychiatrist must treat their mental health for six months and report no abnormalities, be evaluated by FAA approved neuropsychologists and HIMS (Human Interventional Motivation Study) trained psychiatrists, and an HIMS AME must perform a FAA standardized evaluation reporting they deem the pilot fit to fly.

With the awareness that pilots are not seeking mental-health care, the FAA established a Pilot Mental Health Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC). This committee, made up of stakeholders outside the FAA, published 24 recommendations for aeromedical reform to the FAA on April 1, 2024. Since then, the FAA has made several small moves to reform the AME Guide to allow for more mental-health treatments to be issued by AMEs in the field. For example, talk-therapy treatment is still reportable to the FAA, but if the case is deemed to be uncomplicated, the AME can issue a medical certificate. Ultimately, the broader call for reform in the FAA has been met with a culture reluctant to make large, systemic change.

These changes however still leave pilots with medically certifiable mental-health conditions waiting years for one of two FAA psychiatrists from the FAA’s Federal Air Surgeon’s office to clear them to fly. The Air Surgeon has the budget to hire two more staff psychiatrists, but, even by their own admission, this would not clear the backlog. Up to 12 psychiatrists would be needed under their current policies to clear the backlog, and nine would need to remain on staff to keep up with the current mental-health evaluation needs.

Pilot Mental Health Campaign

In the wake of John’s death, and as the voices of pilots suffering under the FAA’s current system have amplified, in the summer of 2023, a small group of aviators and medical professionals formed the Pilot Mental Health Campaign. PMHC is the first and only nonprofit advocacy group in the U.S. advocating for aeromedical reform directly to federal legislators and policymakers in Washington, D.C. Even in the campaign’s infancy, PMHC has achieved success in making pilots’ voices heard at the federal level. In December 2023, PMHC participated in the NTSB Safety Summit on pilot mental health, voicing the consequences of the FAA’s mental-health system. PMHC board members also participated in the Mental Health Aviation Rulemaking Committee, influencing the 24 recommendations made to the FAA. They have also worked with members of Congress to draft legislation, holding the FAA accountable for the aeromedical reforms the aviation community desperately desires.

Through speaking with aviators about the barriers to seeking mental-health care, as well as many of its volunteers going through the special issuance process themselves, the Pilot Mental Health Campaign is actively working towards breaking down the three main barriers that stand before pilots in need of mental-health care—cost, time, and transparency. Far too often, pilots are not being certified due to the extravagant out-of-pocket costs associated with medical certification, the years upon years it takes to reach a final decision from the Federal Air Surgeon, and finally, become so frustrated at the process after being sent letter after letter for documents that are not always published as a requirement for a special issuance by the FAA.

The Pilot Mental Health Campaign’s work has only begun. Feeling the pressure from Congress and PMHC, the FAA has changed some of their mental-health policies, including a new ADHD fast-track policy and new guidance for simple talk-therapy treatments pilots may seek. They have also shown increased support for peer-support groups, allowing pilots to talk about day-to-day stressors with their peers, hopefully stopping that stress from becoming a chronic issue. However, the process for obtaining a special issuance medical has still largely been left untouched, leaving many pilots to fight through the costly, time-consuming, and nontransparent process to return to the skies.

The Pilot Mental Health Campaign lobbying for reform in Washington DC, March 2024. Photo provided by PMHC.

Is it Going to take an Act of Congress?

Members of congress have heard the cries for help from the aviation community and have begun to take action. After hearing John’s story, as well as a similar story from one of his other constituents, Representative Sean Casten, of Illinois’ 6th Congressional District, has introduced the Mental Health in Aviation Act to the House of Representatives. Co-Sponsored by Representative Lori Chavez-DeRemer of Oregon’s 5th Congressional District, this bipartisan piece of legislation has been met with broad support throughout the Aviation Subcommittee on Transportation and Infrastructure in the House. The MHAA would ensure that the FAA is held accountable for the 24 recommendations of the ARC, by placing a two-year timeline on the FAA Administrator to enact those policy changes within the FAA. The MHAA will also establish an annual review of the mental health policies within the FAA, rather than waiting for a tragedy to enact a review of those policies. There will also be a $13.74 million-per-year uplift in the FAA’s budget to increase AME hiring and allow the FAA Administrator to clear the current backlog of certificate applications. Rounding out the MHAA will be a budget for the FAA to then enact a communication campaign aimed toward the aviation community, outlining the changes they have made and clearly communicating to all pilots that they can seek mental-health treatment without fear of certificate deferment or professional repercussions.

Alongside the Mental Health in Aviation Act, Representative Casten and Representative Rudy Yakym of Indiana’s 2nd Congressional District have introduced the Aviation Medication Transparency Act. This is a simple two-page bill that would require the FAA to publish, maintain, and make readily available the list of over-the-counter and prescription medications that pilots may or may not take to maintain their fit-to-fly status. No longer will pilots have to speak with an AME or seek third-party resources to know what medications can or cannot be prescribed by their primary-care doctors during routine care visits. Simple treatments, like an inhaler for a bad cough after a rough cold, can be researched and discussed with a pilot’s primary-care doctor in real time rather than having to delay treatment, research the medication, and then return to potentially be prescribed medication at a later date. This is, yet again, another common-sense fix that should have been available to pilots years ago.

What Next?

The FAA and Federal Air Surgeon have the authority to fully implement the ARC’s 24 recommendations, as well as other broad mental-health reforms. This would dramatically change the culture in which the FAA views pilots with basic, treatable, and safe mental-health diagnoses. However, they have been slow to make these changes. Organizations like the Pilot Mental Health Campaign need further resources and greater grassroots involvement from the aviation and medical industries to work with Congress to hold the FAA accountable.

Recently, the Pilot Mental Health Campaign has enacted an action center to build grassroots advocacy and legislative momentum. Directly from their website, you can input your name and address and have your congressional representative automatically populate. With one more click you can send that representative an email showing your support of the Mental Health in Aviation Act and the Aviation Medication Transparency Act.

Along with digital advocacy, this spring the Pilot Mental Health Campaign will be heading to the nation’s capital to lobby congressional members directly. Building from the 50 volunteers during Lobby Day in 2024, PMHC expects to be even more successful in gaining broad bipartisan support towards mental-health reform. Keep an eye out on social media and email communications for a save-the-date, advocacy training, and other ways to support the campaign for the 2025 Lobby Day.

Together as a community, pilots have shown the need for basic, effective, and safe mental-health care. We have cried out for reforms to make that process take less time, cost less money, and to have a clear, easy-to-access, transparent process published by the FAA. We must keep the pressure on the FAA to continue to update and review their mental-health policies. We must continue proactive advocacy to not have any further tragedies like that which struck the Hauser Family. We must ensure that we hold ourselves accountable to John’s last wish; to change things for the better and help as many people as we possibly can.