Abingdon Welch is a gutsy ball of energy, with bright brown eyes and a perpetual grin. As a pilot, world traveler, and entrepreneur, Abingdon is full of stories about the various people she has met throughout her life, and those who have inspired her to take risks and challenges. After starting Abingdon Co. – the first company created to design watches for women in aviation – Abingdon set up shop at various conventions around the country to sell her wares. Many customers are loyal and have created a connection with Abingdon and her business, and it was one such customer who offered the opportunity of a lifetime.

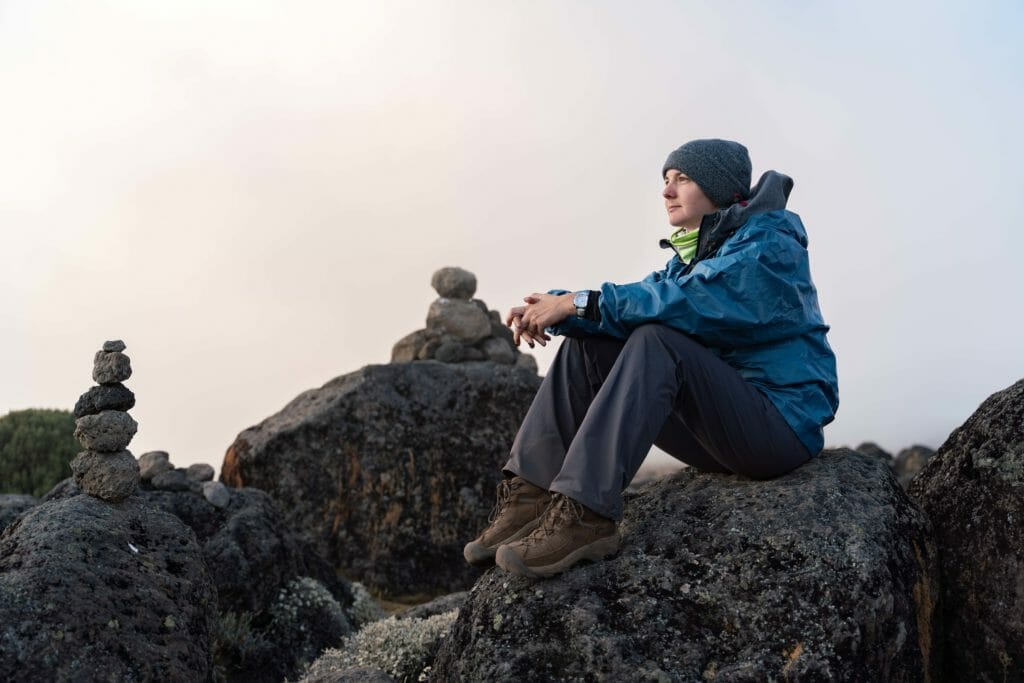

Last spring, at the Women in Aviation conference, as Abingdon prepared to meet new friends and reconnect with old, Colonel Laurel “Buff” Burkel dropped in to say hello. “Buff is a complete badass,” Abingdon shares. “She was a colonel in the Air Force for twenty-seven years, survived a helicopter crash, and has bought a large number of my watches to use throughout her career, so we had developed a kind of neat little friendship over the years.” Colonel Buff was about to make an offer that Abingdon knew she could not resist. “She invited me to her retirement ceremony from the Air Force and she told me I just had to be there, but right before I agreed to go, I realized there was one huge caveat.” The twist? The retirement ceremony was to take place at the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro. Taken aback but nonetheless honored, Abingdon agreed without a second thought. Recalling the moment, Abingdon laughs. “I knew I had to go, but let me tell you, I am not a hiker!” Having only six months to prepare, Abingdon threw herself headfirst into the physical and mental exercises she would need to make it up 19,300 feet to the top of the mountain.

In a group of thirteen individuals, Abingdon was one of three civilians. In addition to preparing for the hike, the group raised $50,000 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. As the time grew closer, Abingdon utilized the mountains in nearby Las Vegas to acclimate to higher altitudes and strengthen her body for the strenuous adventure. In October 2018, Abington boarded a flight to Tanzania to begin the eight-day trek to the top of one of the world’s most difficult summit climbs. It is a six-day walk up the mountain as hikers must slowly acclimate to the thin air, but it is a relatively short day-and-a-half descent back to the bottom.

On day-one of the hike, Abingdon set out with Buff and the rest of the retirement party-goers on the Lemosho Route, one of the six trails used to reach the summit. The Lemosho Route begins on the western side of Mount Kilimanjaro and was started as an alternate to the Shira Route which is a steeper and more challenging trek. On the trail, each person is assigned three porters to carry tents, cooking gear, and various items needed along the way, with the hikers only assuming responsibility of their day bag so they can focus on the physical rigors of the walk up the mountain.

Each morning began with a hearty breakfast prepared by the cooks of eggs or porridge, with coffee, tea, and various breads with jam. The hikers packed a lunch in their day bag and set off for the daily climb. Each leg of the journey is made up of varying mileages, dependent upon the altitude and terrain. Each hiker’s blood oxygen content level was checked before the day’s trek began to ensure health and safety. After breakfast, the porters and cooks climbed ahead of the group to set up a lunch site on the mountain, and at night, the hikers settled in for a hot dinner of pasta, pizza, burgers, or tasty soup before retiring to their shared tents.

On the first night of the hike, while the weather was still beautiful and warm at the bottom of the mountain, Buff summoned Abingdon from the tent to look up at the gorgeous array of stars. “I was standing outside looking up at the stars, totally enamored with Mother Nature, but suddenly I felt a bite on my leg and I was startled. And then, I felt another, and another. I looked down and realized I was standing directly in the middle of an anthill. I literally had ants in my pants!” Abingdon laughs. “I ran back to the tent, tearing myself out of the pants, and Buff came to my rescue, ridding my clothes of forty-three giant black ants! She really saved my life that night.”

Abingdon recalls how the hikers bonded, as if they were a small family despite having come from different backgrounds, ages, and ethnicities. In those moments of the climb, they were all walking toward a common goal.

By day-four, Abingdon noticed that she started feeling slightly sluggish and could barely whip up an appetite for breakfast. After a stint of nausea and upset stomach, she tried to do the daily morning yoga with the group, but found she could barely muster any energy. As is common with climbers of Kilimanjaro, altitude sickness was setting in. The guides placed Abingdon at the front of the line, but a short time into the walk, she had to find a place to be sick in the bushes. “That’s when I knew I was in for a rough time since we had two whole days to go to reach the summit,” she laments. One of the guides stayed with her and walked slowly, even more slowly than the “Pole, pole,” chant heard along the hike. They finally caught up at camp more than two hours behind the group. For the next two days, she would be monitored carefully by the guides, climbing at her own pace. She was determined to make it to the summit for the retirement ceremony.

Twice daily, the entire group was given a series of medical checkups, measuring blood oxygen levels, taking temperatures, and asking a list of questions regarding how each hiker was physically feeling. This was to ensure that each hiker would remain capable of making the day’s climb, and if there were any doubts, the guides would assist in the safe descent of the hiker and medical attention would be administered as quickly as possible. On the day the group was slotted to reach the summit, Abingdon buckled down to make a last ditch effort to reach her goal.

“There is a rule that one can’t summit unless their blood oxygen levels are at least seventy percent. I had learned a trick, that if you sing while your oxygen levels are being taken, it makes them appear higher than they actually are. So. I sang and sang, and I was able to get my oxygen levels to eighty-three percent. Thankfully, they said I was still eligible for the summit hike.” A guide was kept back with Abingdon just in case, and they started the midnight walk to the top of Kilimanjaro.

“Wilfred, that was the name of the guide who walked with me. He and I really bonded during those days and he became like a brother to me. We still keep in touch with each other, and I felt lucky to meet such an amazing human.” Wilfred insisted Abingdon be as safe as possible, even suggesting she come back another time and finish the summit. Abingdon scoffed at the notion and began the hike, joking that she tried to bribe Wilfred for a hit of oxygen from the tanks they carried in case of emergency, but he remained steadfast. “He said, ‘If I give you oxygen, we have to go back down the mountain.’ So I kept climbing, slowly as ever.”

After several, painstaking hours, Abingdon finally made it to the summit, but due to her altitude sickness, she was unable to attend the retirement ceremony for Buff. “Buff said I still made it, but I was so disappointed that I had to be airlifted out of there right at the most crucial moment!” Abingdon was treated for dangerously low blood oxygen levels; she was measured at a mere forty-two percent. “Anything below fifty is nearing cardiac arrest, so I really could have died. I barely remember the walk down to the helicopter pad where I was picked up and flown to a nearby hospital. My body was merely functioning so that I could walk, breathe, and have a heartbeat.” Wilfred had to carry Abingdon on his back the last few feet to the helicopter because her body refused to keep going.

Once at the hospital, Abingdon was given oxygen and hot food, and observed for four hours to ensure she was in the clear and able to be released to go home. While she was able to walk and talk and was not badly injured, upon her arrival in the States, she found out that she also had a parasite and a ruptured cyst. She was on a no-fly restriction at work for a month while she recovered. “I learned the hard way that it takes a very long time to get your body back to normal after putting it through such strenuous circumstances. I was the only one who got a true case of altitude sickness in the entire group, so lucky me!”

In spite of the sickness and strain on her body, Abingdon says being sick was not the defining part of the hike. “I will always remember what it felt like to stand on the summit, the highest point on an entire continent, and to know that the world is my playground. I don’t just want to stay in the sandbox. I want to go out and swing on the monkey bars, to climb on the jungle gym. And while I never anticipated doing this, I always say, ‘Go big or go home.’ I have another chapter to add to my book, and I intend to keep doing it every single day until my life on this earth is done.”

Great story Meredith; I felt like I was right there in the challenge with Abbie and feeling the disappointment of not being able to finish off the challenge by attending the ceremony.

Bert