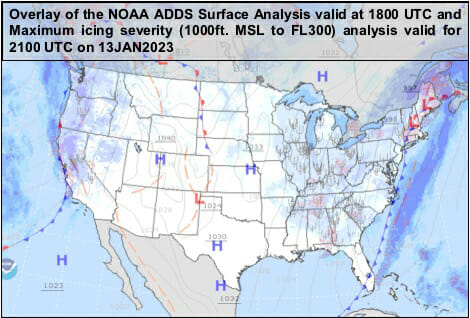

Thunderstorms are one of the most significant hazards to aviation. For instance, on 12 January 2023, a relatively strong cold front dominated the eastern and midwestern United States. This weather system was also responsible for the EF2 tornados in Selma Ala. and the unfortunate loss of human life and property across Alabama and Georgia. Finally, the cold front passed, and as a pilot, you breathe a sigh of relief as the various frontal-related hazards finally pass. As you glance at the radar imagery, you observe those dangerous squall lines and thunderstorms depicted in magenta, red and yellow colors and lightning activity move away from the airport. But, not all hazards departed with the passing of the cold front. For instance, on 13 January 2023, the passing of this cold front paved way for ceiling and visibility obscurations, icing conditions, and turbulence.

Often, the air mass behind the cold front gives way to better flying conditions. Atmospheric pressure rises, and the cooler temperatures improve aircraft and engine performance. The decrease in atmospheric moisture content reduces cloudiness and improves visibility. However, this may not always we the case. For instance, pre-existing moisture and surface evaporation after the passing of the cold front exist in an environment characterized by cooler temperatures. Depending on the ambient air temperature, we can expect cloudiness and either liquid, mixed, or solid precipitation. Supercooled large drop (SLD) may also be encountered in clouds at OAT below 0. Winds are another hazard to aviation and are dynamic around frontal boundaries. The passing of a cold front results in both a direction and speed change. These strong changes in the wind vector are typically associated with gusty conditions, turbulence and windshear. So how can pilots better prepare for flights near weather fronts?

According to the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK, FAA-H-8083-25B), situational awareness (SA) “is the accurate perception and understanding of all the factors and conditions within the five fundamental risk elements (flight, pilot, aircraft, environment, and type of operation that comprise any given aviation situation) that affect safety before, during, and after the flight.” The meteorological conditions near frontal boundaries are complex and depend on the ingredients making up the weather system. Consequently, weather systems may be similar but seldom identical to a past weather event. For instance, an identical frontal pattern over the Great Lakes during late-November vs. late-January will result in significantly different snow-fall totals attributable to Lake Effect Snow. The frozen lakes in late-January reduce the moisture availability and precipitation associated with the weather system.

The PHAK (FAA-H-8083-25B) further elaborates, “monitoring radio communications for traffic, weather discussion, and ATC communication can enhance situational awareness by helping the pilot develop a mental picture of what is happening.” While there is a tendency to emphasize, on the radar image often displayed on TVs, iPads, or smart phones, hazards such as ceilings and visibility, icing, and turbulence may not be directly inferred by just visualizing a radar image. To correct this deficiency and build a better “weather picture,” pilots should review G-AIRMET products and obtain a full weather briefing in order to better understand weather hazards along the route of flight. A pilot’s SA is paramount to the safety of flight and proper pre-flight planning. Obtaining updated weather briefings, and reviewing different types of weather products will help pilots make informed decisions concerning the safety of flight.