Once on the brink of extinction, ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (the Hawaiian language) is now in an era of revitalization energized by a shared dedication to perpetuating the language and the knowledge it bears. This passing of the torch typically peaks in February, when Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language month) is celebrated statewide, including at Hawaiian Airlines.

But this year, the Hawaiian Airlines Community and Cultural Relations team's Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi celebrations are living beyond February, thanks to a new partnership with local nonprofit Awaiaulu.

Since 2003, Awaiaulu has developed educational resources (and people) to bridge Hawaiian knowledge from the past to the present and the future. The group of language experts is training fluent speakers to translate a massive repository of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi texts written before the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893 when the use of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi fizzled as English became the dominant language. Awaiaulu's 20 translators focus on preserving the indigenous knowledge shared in traditional Hawaiian publications, including formal letters, books, manuscripts, government documents and newspapers. The most recent product of its efforts is “Ke Kumu Aupuni: The Foundation of Hawaiian Nationhood,” a robust, bilingual translation of clever, exhaustive newspaper articles written by Samuel Mānaiakalani Kamakau, a 19th-century Hawaiian historian and scholar.

To recognize this Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian Airlines contributed $12,240 to Awaiaulu to fund its donation of 272 copies of the book – which the nonprofit describes as an “invaluable catalog of data about Hawai‘i, Hawaiians, and the nature of national and cultural identity in the Pacific” – to 34 Hawaiian language immersion schools throughout Hawaiʻi. And this week, workgroups across the carrier's network were gifted a copy of the text, including 30 airport stations, its Phoenix IT Center, and its Honolulu-based maintenance and cargo hangar and headquarters.

Manakō Tanaka, senior community and cultural relations specialist at Hawaiian, is proud of his team's work with Awaiaulu and believes the nonprofit is at the helm of “a huge undertaking for Hawaiian history.”

“Throughout the Hawaiian language revitalization movement, which started in the 1970s, people have worked off of the knowledge passed down from their kūpuna (elders) or what’s been shared in English versions of Hawaiian books – which weren’t always translated accurately,” he said.

“So, having ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi speakers translate and create access to the information in these newspapers and documents opens up an entirely new library of knowledge for current and future generations. Those documents give us insight into the kūpuna of our kūpuna, and they are the oldest resources that we have to look back on when we try to understand what our kūpuna were doing and thinking.”

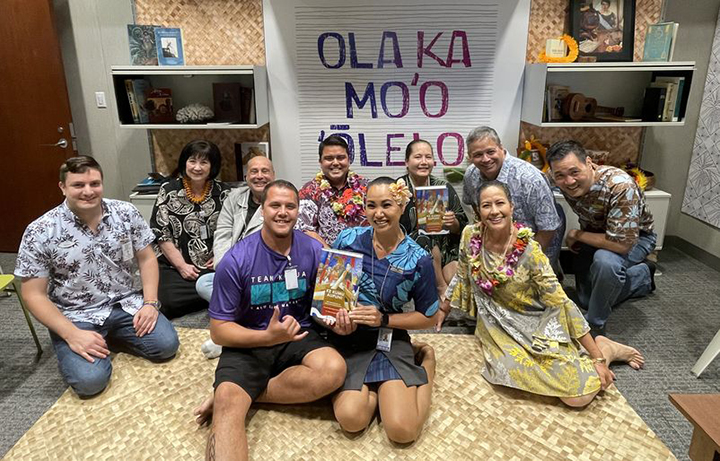

Aside from the book donation, Hawaiian also engaged its employees and guests with a series of special Mahina ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi activities, including an ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi roundtrip flight between Kahului, Maui, and Las Vegas with certified ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi-speaking flight attendants. Employees also volunteered at Ola Ka ʻĪ (The Language Thrives), a series of three Hawaiian language gatherings organized by a group of local nonprofits at Oʻahu’s Windward Mall and Ka Makana Aliʻi, and the Queen Kaʻahumanu Center on Maui. The Hawaiian Airlines Serenaders performed live music and hula at the Ola Ka ʻĪ events as volunteers hosted arts and crafts, including a new coloring sheet that identifies the ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi names for the parts of the Airbus A330 aircraft — Hawaiian’s flagship aircraft.

Employees also joined an ‘Imi ʻIke (to seek knowledge) session that shared ʻike (knowledge) and moʻolelo (stories) from community leaders, like Awaiaulu’s executive director, Puakea Nogelmeier. They listened to Nogelmeier’s manaʻo (thoughts) and moʻolelo (stories) behind his team’s grueling but impassioned work translating millions of pages of text, one word at a time, and with the historical context in mind. “Our work is not about language; it’s about knowledge. We are not re-writing history; we are putting the color in the black and white,” he said.

Nogelmeier elaborated, “Kamakau wrote in a language that was intentionally clear, so the Hawaiian he used was good quality Hawaiian for his time.” He held up the book to the group and teased its weight resulting from pages written in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and a meticulously translated English version. “This is a teaching text. It is meant to educate and create access to the Hawaiian language. You should read the book in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi first and then use the English version to affirm your understanding.”

Tanaka said, “We want to proliferate Hawaiian knowledge within our ʻohana by creating opportunities for non-speakers to learn and use ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi every day. By sharing the book with schools and our employees, we can further those efforts while also helping Awaiaulu make the knowledge of our kūpuna more accessible to the masses.”