Should I stay or should I go now?

Should I stay or should I go now?

If I go, there will be trouble,

If I stay, it will be double,

So come on and let me know,

Should I stay or should I go? (Clash, 1994)

These immortal lyrics from the 90s-era rock band The Clash present the dilemma facing many pilots in business aviation: should they stay in business aviation or transition to the airlines? While there are many things to consider in that decision, most people drill down to two primary items: money and quality of life. In the paragraphs that follow, we’ll briefly examine these two.

First, full disclosure, when I was retiring from the Air Force in 2001 from Luke Air Force Base outside of Phoenix, several of my compatriots had made the transition to Southwest Airlines. This was at a time when if you knew someone at Southwest and they vouched for you, a job offer usually followed. I’d see these guys on base in the gym or at the officer’s club. Southwest had its own Crud team. (If you don’t know what Crud is, you’re probably better off!) I’d ask them about life in the airlines and frankly, the more they told me, the more it bored me. So, perhaps I’m a little biased. Anyway. . .

The Money

If money is the primary consideration in your aviation career, and if you’ve got a fair amount of life-runway before you reach 65, you can stop reading here – just go to the airlines. With the latest contracts signed by pilots’ unions for Delta, American, United, and Southwest, the amount of money a pilot can make over their career can get into eight figures. Unless a pilot transitions to a well-paying director role in a Fortune-500 company, they will probably never make that much money in a business aviation career. When I provide consulting advice to aviation managers, it’s pretty direct. I tell them they can’t pay what the airlines can, and they shouldn’t try. Instead, I tell them to pay enough to create uncertainty. This uncertainty factor is something pilots should consider as well.

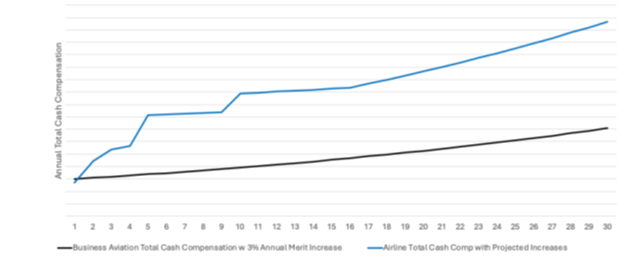

Figure 1. Airline Compensation vs. Mid-Level Total Cash Compensation

Figure 1 graphs a starting mid-level of business aviation compensation vs. the compensation level for an actual major airline. We see a very low level of uncertainty. A pilot can leave their corporate job and within two years regain the previous level of compensation and lose very little money in the transition. I can’t depict the actual starting number for the graph because of price-fixing concerns and the airline graph makes several assumptions about upgrades, but the path depicted by the two lines is accurate. At lower- to mid-levels of business aviation compensation, the decision to transition to major airlines is a no-brainer decision if cash is the primary consideration.

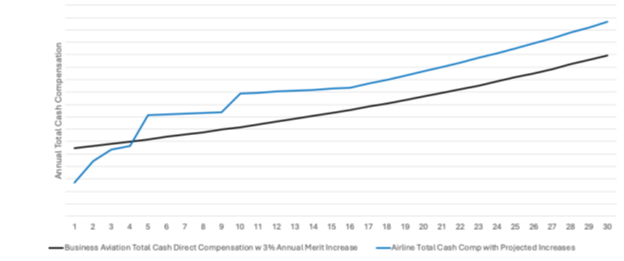

Figure 2. Airline Compensation vs. Higher Total Cash Compensation

Now if we raise the compensation level, a different situation occurs. The pilot here won’t regain their previous level of compensation until Year 5 and won’t recover the money lost in the transition until Year 8. That’s a lot of uncertainty. If the pilot has kids in middle school or high school and is looking at paying for college, the pay cut may not be acceptable. There are many combinations of pilot age and higher compensation levels that create situations that push the intersection point far enough to the right where an airline transition doesn’t make sense. One of my talking points for aviation managers has been to not put their pilots into a position where they appear financially irresponsible in discussions they have with their spouses, and that means pushing the intersection to the right as much as they can.

Quality of Life

In 2017, I conducted a scientific study that examined why pilots were leaving business aviation for the airlines. In that research, I determined that quality of life was the number one factor in that decision, followed closely by compensation (Broyhill, 2017). In that study, quality of life was essentially defined as a function of the predictability of life. Could a pilot make plans to be at events for their spouse or children and actually show up? Unless a pilot flies for a fractional operator, this is a condition rarely seen in business aviation. Corporations and high-net-worth individuals pay for the availability of their pilots, so schedules are hard to come by. In contrast, once a pilot reaches a certain seniority level in the airlines, they will be able to plan their life. Obviously, there will times in which the pilot is forced to bid reserve (like being on-call) as seniority builds. But once that period is over, they can largely work the scheduling system in their favor. There are some caveats here, however. If a pilot is home-based, i.e. living in the city where their trips originate, life and scheduling can be very good indeed. But if they have to commute to the city/airport where the trips originate, that’s another situation entirely and the amount of time it takes makes it like a second job. To quote a former airline pilot now in business aviation, “This has really hit a few of the business aviation guys hard. It’s a big thing.”

Obviously, this has been very brief look at the decision process for business aviation pilots as they contemplate a major career transition. But if we stop here, the discussion would be incomplete. The reason many pilots stay with business aviation is because they love the job itself. And that is something we’ll discuss in the next article.

Bibliography

Broyhill, C. &. (2017). Pilot Workforce Retention Exploratory Study. Washington DC: National Business Aviation Association.

Clash, T. (1994). Should I Stay or Should I Go. Retrieved from Genius.com: https://genius.com/The-clash-should-i-stay-or-should-i-go-lyrics