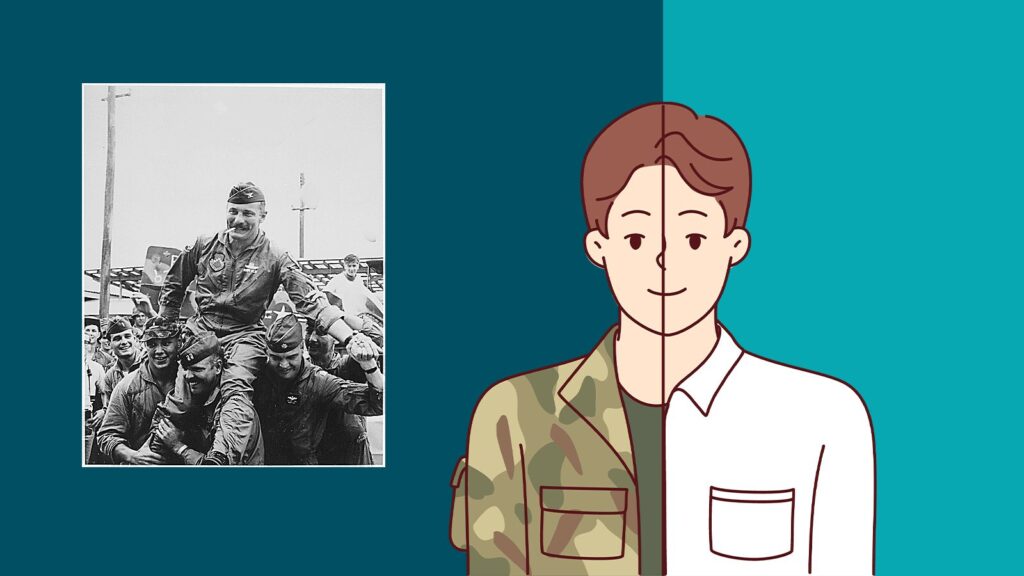

Wolfpack pilots of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing sweep Colonel Robin Olds away from his F-4 Phantom II aircraft following his return from his 100th combat mission over North Vietnam. Olds led the Wolfpack through the past year as it amassed 24 MiG victories, the greatest aerial combat record of an F-4 Wing in the Vietnam war.

// U.S. National Archives Catalog

This article will be a segue from my usual topics this month as I turn to a discussion about leadership. I don’t write about this subject often. Not because I don’t have some strong opinions on leadership—I do, but because there are so many books, articles, and social media posts about it that it’s easy to become inundated with information. I’m also somewhat jaded by the repeated banal posts about leadership that I read on LinkedIn, the only social media I regularly consume. It seems like anyone and everyone has the inside track on what makes or breaks a good leader and are only too eager to bestow their sage wisdom on us, the ignorant masses.

Before I go on, without being immodest, let me list a few of my credentials so you’ll understand I haven’t been a mere observer/analyst of leadership; I’ve also been a practitioner for most of my adult life. I spent over 20 years in the Air Force, mainly at the squadron level, and have held nearly every leadership job there. In the fighter world, I was checked out at the mission-commander level, which means I could lead up to sixty aircraft into battle. Since transitioning to business aviation after I retired from the service in 2001, I’ve held almost every operational leadership job in the industry on both the Part 91 and Part 135 sides, culminating in the Director of Aviation role for a Fortune 100 energy company.

Okay—enough chest beating. The point with the abbreviated bio is that I’ve done my fair share of leading and following in the military and civilian arenas. The biggest lesson I’ve learned should seem obvious but often isn’t emphasized enough. Military and civilian leadership ARE DIFFERENT! On the military side, particularly if you’re in a role that could see combat, you have the “unlimited liability” clause, in that you may intentionally lead others into harm’s way, and there is a non-zero probability that it could cost you your life. You also don’t have the option to refuse. If you’re given a lawful order, you must obey it or face court martial. On the civilian side, neither of these conditions is true. While there are undoubtedly hazardous jobs in the civilian sector, none require you to deal with enemy fire as you perform them. And, if you wake up one day and decide not to do what your boss asks you, you can say no and leave the job. It is hard to overstate how much this difference can affect leadership styles.

Then, there is the difference in those who are led. In a typical military combat unit, you have highly motivated personnel who all want to be there, want the unit to succeed, and will go the extra mile to make that happen. In a civilian organization, subordinate attitudes can run the gamut. Some will want to be there and operate at a very high level. Others couldn’t care less and will do the minimum required to earn their salaries. Each group requires different leadership skills and styles.

For my first few years after retiring from the Air Force, I worked in various leadership roles for a few different charter/management companies, including one that I started myself. Thanks to my military experience, I thought I knew everything there was to know about leadership. I could not have been more wrong. It took me about five years to put my military leadership experience into a perspective where it became useful on the civilian side. Perhaps the other biggest thing I realized is a practical restatement of one of the things I said above. In the military world, people have to follow you. In the civilian world, they have to want to follow you. Don’t get me wrong, on the military side, it’s better if they want to follow you, but the “want” isn’t necessary to get the mission done. On the civilian side, the “want” is essential.

So, where am I going with all of this? I can’t tell you how many LinkedIn posts I’ve read written by those who left the military, never held a civilian job, and are only too willing to offer civilians advice on how to lead. My favorites are those who have turned their military experience into a business where they provide that “service.” Maybe today’s military is a kinder and gentler place than it was when I was in, but it obviously took me a fair amount of time to understand the applicability of my military leadership skills in the context of a civilian leadership position. I’m not sure how those who offer military leadership advice without “walking in the civilian moccasins” have the scope of understanding needed to gain perspective on that advice.

Let me offer some advice of my own to my military brothers and sisters who are making the transition to a civilian job or considering it. It’s the same advice I used to give young captains or lieutenants who were leaving the training squadron and going into the operational world. For the first three months after you get to the new organization, eyes open, mouth shut. Watch and listen. Don’t be too eager to offer your observations. Learn the organization, learn the leadership, learn the culture, and understand the dynamics of the environment. Only then will you be in a place where you can understand how your leadership experience can be applied there.

Having gone on my semi-rant about military vs. civilian leadership, I have to say a few words here about one of my heroes, the great General Robin Olds. His exploits are legendary, perhaps the most famous being leading Operation Bolo in Vietnam, where his wing imitated the formations and call signs of F-105 fighter-bombers to lure North Vietnamese MiG-21s into the air. The plan worked; the MiGs came up to play, and the F-4 pilots of the famed Wolfpack smacked them down. Olds was perhaps the last great combat leader the Air Force has produced, and his biography, Fighter Pilot, written by his daughter, Christina, is one of the best I’ve ever read. It is worth your time. Olds was a leader like few others I’ve encountered in my career because he possessed that rare talent that I mentioned above: you followed him because you wanted to, not because you had to. And at the end of the day, that’s the one ability all leaders, military or civilian, should strive for.