Our subject this month is tropical cyclones. Rather than delve deeply into myriad reasons behind the formation of tropical cyclones (e.g. hurricanes and related systems), I will differentiate between the various kinds of basic tropical systems. This basic review will lead to a discussion of one particular variation of a tropical cyclone, namely an extratropical cyclone. In doing so, I hope this article will serve as a catalyst to adjust your pre- and in-flight decision making when the indicators are that the hurricane has weakened into non-existence.

Tropical Cyclone 101

Tropical cyclones (low pressure areas) begin their lives in various tropical regions of the world. Depending over which body of water they form, they are either referred to as hurricanes or typhoons. Hurricanes are born in the Atlantic. Typhoons are born in the Pacific. Henceforth, I will be referencing Atlantic systems in this article.

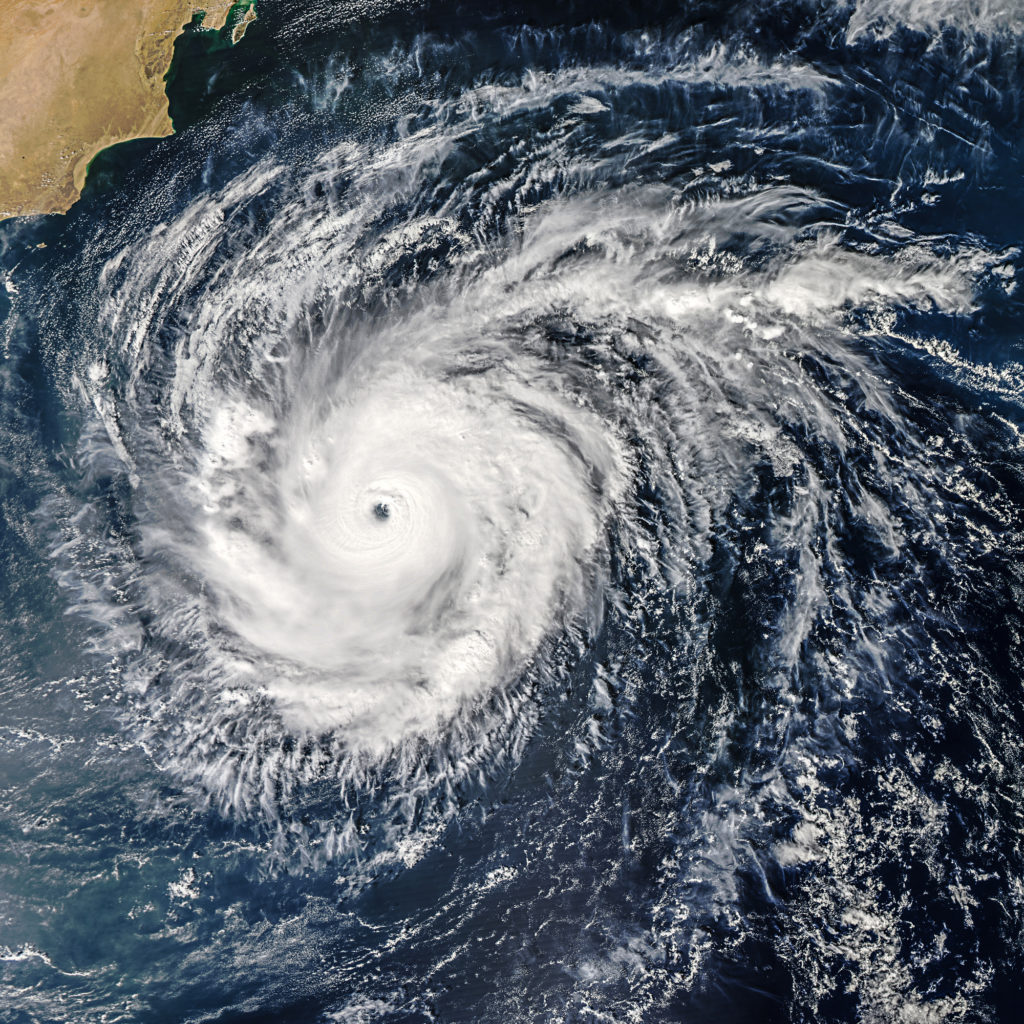

The evolution of a hurricane begins with tropical waves, then becoming tropical depressions and ultimately developing into a hurricane. Each phase of the overall tropical system development is defined by sustained wind speeds and circulation (or lack thereof) within the system. An area of tropical low pressure with sustained winds up to 39 mph is considered a tropical depression. An area of low pressure with wind speeds of 40-74 mph is a tropical storm. Finally, an area of tropical vorticity with wind speeds in excess of 74 mph is a hurricane. Vorticity is rotation or spin in the atmosphere, or spin.

Another key ingredient in tropical storm or hurricane development is circulation. If the disturbance includes circulation, then it is either a tropical storm or hurricane depending on its sustained wind speed. The distinction between these two weather phenomena is discernable circulation. A tropical depression has no circulation or very poorly defined circulation.

A hurricane is nature’s attempt to restore balance to climate. Said another way, the persistent heating of tropical waters requires that nature dispose of this energy in some way. Hurricanes are that way.

Extratropical systems

When it comes to hurricanes and flying, the subject is generally pretty simple – we don’t. Let’s address extratropical cyclones and what we should consider when faced with flying near, in or around one. Extratropical cyclones can be a further evolution of a hurricane. In a sense, they can be part of the process of how hurricanes die. Once a hurricane has lost its status and notoriety (i.e. it weakens), it might seem okay to fly into or around the remnants. The following are some examples of systems that were extraordinarily dangerous despite either not being cyclones or having been cyclones that entered extratropical storm status

- Hurricane Hazel. 1954.

- Columbus Day Storm. 1962. Washington State and Oregon.

- November 10, 1975. The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

- December 14, 1985. Iceland. An area of low pressure developed that was so intense it achieved barometric pressure equal to a category five hurricane. I bet it was really windy that day! This was not a hurricane.

- Hurricane Wilma. 2005.

An extratropical cyclone has its origins in hurricanes. When a hurricane has begun to morph into a “cold core” system versus a “warm core” system, the transformation to extratropical has begun. This happens when the hurricane begins to move into higher latitudes. The process by which a hurricane takes on different characteristics from its original form is key to how it relates to us in an airplane.

By definition, an extratropical low is a large-scale low-pressure system that occurs in midlatitudes. Technically, it does not require a hurricane to be the root of its existence. That said, hurricanes are certainly a good starting point for one to form. Among the features of these systems that could be hazardous to airplanes are:

- Bombogenesis and negative tilting

- High winds – sustained and gusts even after the hurricane dies due to deepening of the low.

- Baroclinic zones – areas of starkly contrasting temperatures/temperature gradients in the extreme. Tremendous instability can result (e.g. wind shear). This is often the case when the system achieves a cold core and then passes over warm water.

- Thunderstorms

As pilots, we need to be on guard. We need remain vigilant once a hurricane has come inland. We need to be very mindful of the many hazards and intensity that sometimes accompany a weakening hurricane. We need to be very careful of where and when we fly our trusty aircraft. This kind of system is not necessarily your garden-variety low pressure.