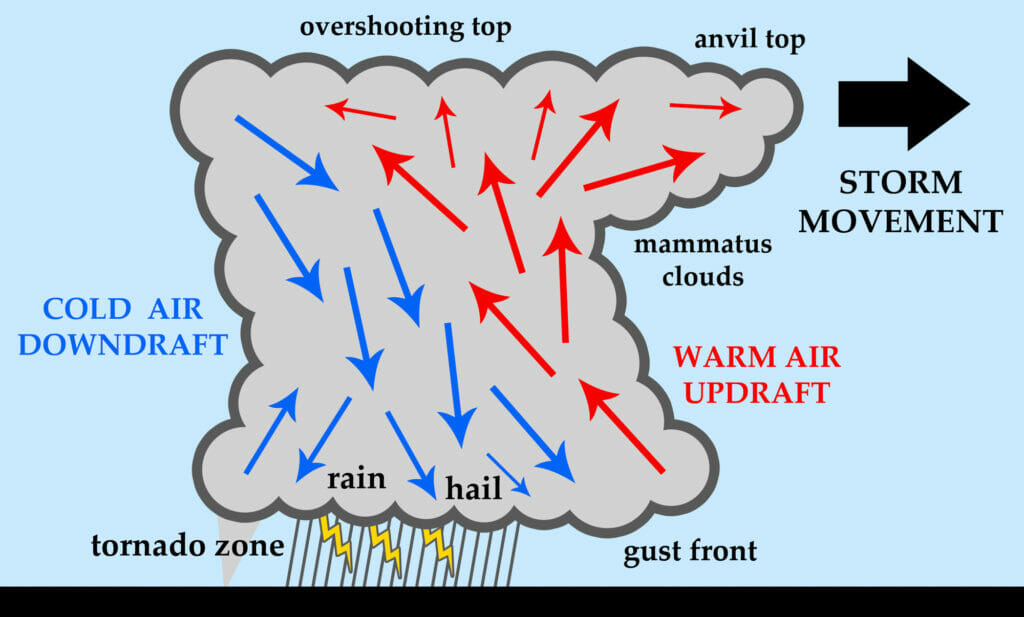

An outflow boundary is also known as a “gust front.” No doubt, each of us knows the importance of recognizing a gust front and have all seen one while on the ground watching that windsock in utter amazement! A gust front is a sudden uptick in winds resulting from an approaching thunderstorm. But there is more. This uptick in winds, from the general direction of an approaching thunderstorm, is the result of a downdraft hitting the ground and spreading out horizontally. Recall that this alone can be extremely hazardous to aircraft operations. Still, there is even more!

At times, if a gust front has enough energy or momentum, it can march on for quite some time and distance. Since energy does not just go away and wind is energy, it dissipates but turns into something else. Occasionally, the gust front lasts long enough interacting with the environmental (moisture, frontal boundaries, temperature gradients, etc.) and geographic conditions in such a way that it contributes to the formation of clouds, rain and possibly additional storms.

WHAT DO YOU SEE?

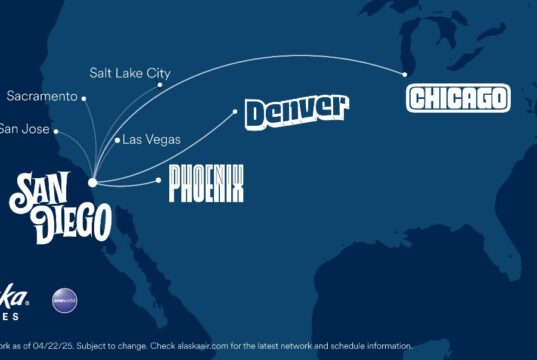

Prominent outflow boundaries are often visible in two ways, satellite and radar imagery, affording the astute pilot opportunity to make informed pre-flight and in-flight decisions. Learn to recognize them and know what is behind them can be benefit you as a pilot. These outflows can be a breeding ground for new weather formation that can occur just a short time after the outflow was born – several hours later or even a day later. In a very real way, outflow boundaries set the stage for where severe weather might develop next. Be aware that these are mesoscale and not synoptic events. Rarely will you find them on a chart. You must look elsewhere.

Often, radar imagery will show green echoes in arc form ahead of a larger area of precipitation. You are not going to be impressed by the intensity of the echoes (dBZ) of the outflow radar return enough to circumnavigate, but this can be a warning. You might be impressed by the magnitude of the winds present in the vicinity of this outflow radar return while you take off (or land), as well as the flare-up of new thunderstorm activity in the area. This is your evidence of why you see increased convective weather.

In addition to radar, satellite imagery can also cue you to the existence of an outflow boundary. Look for one or more bands, sometimes in arc form, of clouds (primarily cumulus) that have formed out ahead of more formidable weather. This could be your next hot spot.

A MORE THOROUGH PRE-FLIGHT

I don’t suggest that you steer away from these phenomena while in flight but want you to be aware of their potential for danger, primarily before you take flight. Outflow boundaries can be hazardous in two ways despite being benign-looking areas of precipitation. Once you can recognize them you can see that they could represent strong surface winds and a birthing area for new convection.

With every flight you take, you have the opportunity to see what you are getting into – the weather briefing. Use your knowledge to be proactive in various circumstances and become savvy enough to look for hazards and use the right tools to find them. Your radar and satellite images are your allies.